By Ben Sichel. Ben is a teacher in Dartmouth and author of the P-12 education section for the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives’ Alternative Provincial Budget. Originally published at no need to raise your hand.

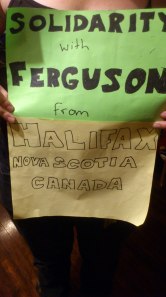

There’s a rally in Halifax this Tuesday in solidarity with the people of Ferguson, Missouri, and all black youth.

If you’re a teacher, I’d like to encourage you to attend.

I won’t re-hash here the

details

of Ferguson teenager Mike Brown’s killing by police officer

Darren Wilson, or the subsequent wave of protest that showcased

the

militarization

of U.S. police for the whole world to see.

I won’t re-hash here the

details

of Ferguson teenager Mike Brown’s killing by police officer

Darren Wilson, or the subsequent wave of protest that showcased

the

militarization

of U.S. police for the whole world to see.

The rallies and demonstrations taking place around North America in response to this incident are reminders (for those of us who have the privilege occasionally to forget) of the centuries-old patterns of anti-black racism* that continue to plague our society.

In the wake of Mike Brown’s death, more of us are learning statistics that illustrate this, like the fact that more than 300 black American men were killed by police in 2012, or that the median black family’s wealth is 1/20 that of the median white family.

Here in Canada our conversations about race are more muted, probably due at least in part to our preferred national image as the place where enslaved African-Americans came for freedom – after fighting for the British in the Revolutionary War and the War of 1812, and on the Underground Railroad.

The full picture is much more…spotty, to put it kindly. The first major wave of Black immigrants who came to Nova Scotia in the late 1700’s faced such fierce racism that most of them left within a decade. American Jim Crow laws were often mirrored in Canada, with segregated institutions mandated by law from the mid 1800’s (at the height of the Underground Railroad) to the mid-1900’s, when civil rights heroes like Viola Desmond actively challenged them. In the 1910’s and 20’s, governments attempted all sorts of chicanery to stem a feared tide of black immigrants from Oklahoma, including stating that Black people were “unsuitable to the climate and requirements of Canada.” [PDF link to an interesting “Historical perspective on anti-black racism in Canada”]

The late 1980’s and early 1990’s saw very public incidents of flaring racial tensions, leading to reports such as the Stephen Lewis Report on Race Relations in Ontario (1992) and the BLAC Report on Education in Nova Scotia (1994). Both reports spelled out the details of anti-Black racism in their respective province’s institutions and made recommendations for change. These recommendations have been implemented to varying degrees over the past 20 years (the last comprehensive evaluation of the BLAC report’s recommendations was done in 2009; that report is available here (PDF)).

As teachers, we need to recognize where our students are coming from. For our African Nova Scotian students, this means understanding that they live in a world where they are disproportionately suspended from school, put on special education plans, and incarcerated. We need to examine honestly the reasons for these inequities, listen to our students (as well as our colleagues and friends) when they tell us about incidents of racism, and do the hard work needed to address them.

And we need to encourage and support our students when they take the lead in the fight. Let’s start by showing up on Tuesday.

*

This isn’t to say that other forms of racism are more or less

important than anti-black racism; it’s simply to note that

different forms of racism are qualitatively different from one

another.

Note: Articles published by Solidarity Halifax members do not necessarily reflect positions held by the organization.