By Ben Sichel. Originally published at

no need to raise your hand

Ben is a teacher in Dartmouth and author of the P-12 education

section for the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives’

Alternative Provincial Budget.

A few weeks ago, Halifax journalist Tim Bousquet wrote a brief piece about the history of slavery in Nova Scotia. Bousquet pointed to an article by University of Vermont history professor Harvey Amani Whitfield which contends that slavery was further widespread here than official statistics suggest:

Whitfield shows that slavery was widespread, found in every part of Nova Scotia, and that sales of slaves, including children, and notices of runaway slaves were regular features in local newspapers.

Whitfield gives only a preliminary sketch of the extent of slavery, and says while more work is needed, the total number of Nova Scotian slaves will never be known. But Whitfield thinks that historian James Walker’s figure of 1,232 Nova Scotian slaves is far too low.”

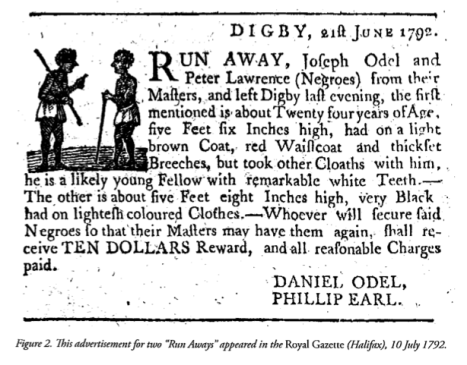

Whitfield’s article featured pictures of old newspaper ads announcing rewards for escaped Africans, like this one:

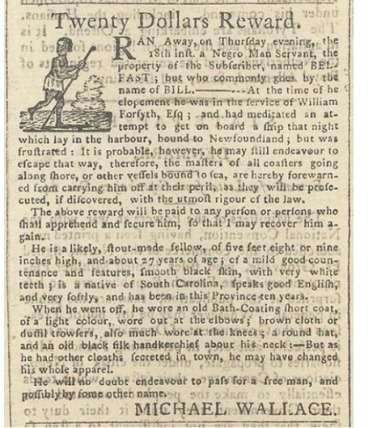

Seeing them reminded me of this similar image, from 1794, which

is on display at the Africville museum in the north end of

Halifax:

Seeing them reminded me of this similar image, from 1794, which

is on display at the Africville museum in the north end of

Halifax:

Last fall, I brought my class on a field trip there, and while a museum guide explained the history of slavery in this province, a student pointed to the name on the bottom of the ad and asked “is that the same Michael Wallace who my elementary school was named after?”

The guide and I looked at each other, and we both had to admit we didn’t know anything about the historical figure of that name. A quick Google search, though, told me that the Michael Wallace for whom a Dartmouth school is named was a Scottish-born businessman and politician best known for spearheading the construction of the Shubenacadie Canal.

The few written pieces on him didn’t mention slavery, however, so I wrote to David Sutherland, a Dalhousie history professor who wrote Wallace’s entryin the Dictionary of Canadian Biography, and asked if he thought the Michael Wallace he’d written about was the same person named on the poster at the Africville museum. It most likely was, said Sutherland:

“[It]’s not surprising [that Wallace owned slaves] given his many-faceted involvement in business. Of particular interest is the fact that Wallace was hiring out his slaves (assuming he had more than one) to work for others…

Wallace, for reasons I go into in considerable depth in the DCB profile, was a highly controversial figure. But the fact that he owned slaves in the 1790s was not one of the reasons why he was unpopular among most of his contemporaries.”

All this got me thinking back to the Halifax Regional School Board’s decision in 2011 to re-name Cornwallis junior high school, based on that British colonial general’s treatment of the Mi’kmaq people. While the board’s decision in that case was unanimous, the public’s reaction to it was decidedly not. Outraged commentary appeared on letters pages, in op-eds and on call-in shows claiming the decision was political correctness gone amok.

One of their arguments, common in this type of debate, goes something like this: No historical figure was perfect. We can’t start re-naming everything that might offend someone. Where would it stop?

It’s true that an effort to acknowledge historical wrongs could involve an awful lot of re-naming. The town of Amherst, Nova Scotia, for example, is named for Jeffery Amherst, a British Commander-in-Chief who advocated for the distribution of smallpox-infested blankets to Indigenous people. General Robert Monckton, namesake of New Brunswick’s largest city, is known for his leading role in the deportation of the Acadians. The Earl of Dalhousie, for whom my alma mater is named, tried (and mostly failed) to rid Nova Scotia of the Black Refugees who had come here seeking freedom following the War of 1812. Re-naming things named after figures with skeletons in their closets would certainly require some very deliberate work.

But so what? Re-naming everything is exactly what British (and French) colonists did as they forcibly took over this land and extracted its wealth for the benefit of their empires, at the expense of its original inhabitants and enslaved peoples, for centuries thereafter. Are these colonists’ legacies worth honouring by putting their names on public monuments? All levels of government have talked in recent years of reconciliation and new partnerships; no one ever said those things were easy.

Some say re-naming public works would be akin to re-writing history. But calls to maintain the supposed integrity of history are most often about maintaining the status quo – history taught from the perspective of the winners. When history is inconvenient to us; when instead of glorifying our ancestors it forces us to grapple with the effects of past wrongs – lower standards of living, based on many socioeconomic indicators, for Aboriginal peopleand African Canadians – we try to ignore it and tell people to “get over the past.”

Granted, some legacies are complicated. According to historian David Sutherland, Michael Wallace was, in addition to being an owner of enslaved Africans, the agent responsible for coordinating passage overseas for the nearly 1200 Black Loyalists fleeing the racism and general hardship of Nova Scotia for Sierra Leone in 1792 (a fictionalized account of this exodus is in Lawrence Hill’s novel The Book of Negroes). At the time, the exodus to Sierra Leone was opposed by most local white elites, who enjoyed the pool of cheap, easily exploitable labour the Black Loyalists provided. “That’s a story your students should know about,” Sutherland told me.

The names we use on public works to decide which figures in our history are worthy of honour tells us much about our values. Although some stories (like, for example, that of Burton Ettinger School in Fairview, named for a late school custodian reportedly beloved by all) are not as complicated as that of Michael Wallace, we shouldn’t be afraid to take a good look at those that are.

Note: Articles published by Solidarity Halifax members do not necessarily reflect positions held by the organization.